Editor's note: I meant to make some basic edits to this post, which I worked hard to create, but then ended up deleting it. Oh noes! Luckily, though, I recreated it from my Google Reader feed.

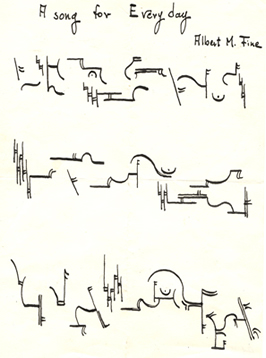

The image to the right is a composition by Albert M. Fine (linked to the UI Special Collections department).

Okay, I will just state outright that goofy, aleatory music from the 1960s is some of the most dated art ever, and it can be unapologetically, unendingly tedious. I've talked about in general in the second half of this post. Nonetheless, as a musicologist training in Iowa City, I've been spending some time in the Albert M. Fine papers in the University of Iowa Special Collection Department's Alternative Traditions in the Contemporary Arts holdings. I first started poking around in the archives during the spring of '07, then didn't for awhile, but now revisited it looking for unpublished material to use as Music Editing exercises.

Archives are good for hording, right? But in the name of collective interest, maybe I'll put a teaser to what can be found here out here on the internet in the hopes that some researcher may have some more information on Fine, and so something musical will appear when you google "Albert M. Fine".

Fine was a clarinetist in an Armed Forces service band stationed in Paris during the early 1950s, where he befriended Ned Rorem (a few of whose letters, tame in light of his voluminous personal writings, of which Mescaline in the Poconos is the most entertaining, appear in the archive) among others. Fine trained at Julliard under Vincent Persichetti (who is a prime example of a composer who we play but seldom talk about. Philip Glass's Grove Article (and if you're still reading by now, you're probably the type who would have access to a Grove proxy log-in) by Edward Strickland lists Fine as a student of Boulanger (which makes sense, given the Rorem/Paris years in the early 1950s) as well as one of Glass's private teachers while they were fellow students under Persichetti.

Before Glass moved to Pittsburgh, he worked at the Yale Transport Company as a "pusher," a fact proved by the identification badge of a thuggish looking pretty-boy, "P. Glass," that Glass mailed to Fine, who had loaned Glass some money previously. Glass's letters are

particularly funny, especially when he refers to the many "block-heads" at Aspen and "boobys" among New York's composers in the summer of 1960. A roll of four mini-photos of a goofy Glass apparently taken in an amusement park's photobooth is worth the price of a Greyhound ticket to Iowa City.

particularly funny, especially when he refers to the many "block-heads" at Aspen and "boobys" among New York's composers in the summer of 1960. A roll of four mini-photos of a goofy Glass apparently taken in an amusement park's photobooth is worth the price of a Greyhound ticket to Iowa City.Also of musical interest: a genial Christmas card from the early 1960s reading "Peter Schikele, Hollywood Composer" where the future P.D.Q. Bach wonders aloud if he'll ever find his niche. (Hint: he did.)

Also of note:

- support from budding young IBM mathemetician NY Phil assistant conductor Stefan Bauer-Mengelberg

- a fascinating correspondence between a semi-famous Soviet conductor, Fine Persichetti, and the Lincoln Center's impresario Mark Schubart that I'll only tease for now (Would that I read Russian), except to say that Persichetti, through his publishing outlets, helped to funnel new-music scores into the USSR during the heyday of the Khruschev thaw. There is a wish-list (David Diamond was the talk of the town) and letters of receipt.

- There are letters to Cage, and typescripts/early scores from LaMonte Young that are the subject of a separate meme.

Fine's scores, largely unpublished, align with some of my recent Taruskin reading that deftly seeks to challenge the way our "histories" are simply chronicles of firsts this, firsts that, and puts anything perceived as "regressive" off to the side. Interspersed in his dated compositions (spanning six years in the early 1960s) are:

- ballet scores for David Waring in the vein of Persichetti (wherein "neo-classic" wind textures frame sonorous but non-tonal melodies)

- eminently playable solo and chamber works for woodwinds that also recall Persichetti's Parables in their idiom

- silly, self-referential songs

- piano works that show the influence of Cage and Feldman (particularly in the way that spatial organization on the score is a device of rhythmic notation)

- Silly, irreverent miniatures (including a horn quartet with a variety of pseudo-Germanic dedications)

- "Game" pieces that experiment in open form according to parameters

- (contains profanity) early fluxus scores, including a notated "happening" for the Longy School of Music in 1965 (that ends with a young girl exhorting the audience: "Dear Audience, Fuck You, You are Now invited to Bug Out.”

- Works from 1965 for pianist David Tudor that are nothing more or less than early minimalism (not "proto-minimalism"), where two constant broken pentatonic "cells," a half-step apart repeat for 30-40 measures at a time and slowly change.

Think, for a moment, on the notion of a fully-notated happening in 1965, the golden-age of happenings, at the Longy School of Music. Even by 1965, this far-out technique was just that: a commodified technique, a set of formal principles useful for generating more music. But looking at one man's unpublished output from this time period, something stands out: the same man is, in the same month, producing music that questions the nature of music and writing eminently playable, impeccably notated, downright neo-classic works by comparison to Fine's work for "24-piece Fluxorchestra."

On the one hand, the score is becoming a visual document rather than an aural schematic; on the other, his friends and colleagues want some music to play and to dance to. Playing-Music and Talking Music. What better way to prove Cage's ascendancy--not to mention the way he's become defanged--than to notice that his dictums were, and are, just another compositional technique? But if this music were to make it out of that archive in scholarly form, which do you think would attract the most notice from scholars, and which from performers?

Like the other minor American composer that I'm researching, William Russell, Albert Fine has been (and will continue to be) a minor prophet unless one makes him into a John the Baptist for a coming Jesus (John Cage, Steve Reich, etc.). Each composer's career nicely bookends Cage's main period of musical creativity (with the exception of some string quartets in the 1980s), anticipating it, perhaps, and reacting to it, perhaps. Each dabbled in the avant-garde styles of their day, even exhibiting some avant-garde predilection for "firsts," before withdrawing to greener (or, in Fine's case, more "cosmic") pastures. Each had a brief and modest compositional output and probably have, in the process of historical darwinism, died their natural deaths.

Fine went on to be more well-known as a visual/conceptual artist. Indeed, his name is listed in a "mail-art" directory from the early 1970s, so among his correspondence are several crude drawings and unexplained postcards from strangers, including a lovely drawing of an afternoon sky by poet Allen Ginsberg and, tellingly, a pornographic playing card featuring a pantsless cowboy sent mailed without enclosure or comment (just return address) from debatably pornographic photographer/right-wing Bogeyman Robert Mapplethorpe in 1970.

Fine seemed to live the boundaries of the question, "But is it art?" and seemed to relish "freaking out the squares." For a couple hours the past couple Friday afternoons, I've put myself in Cambridge during the 1960s, and, leafing through the thick of it, minimalism, flute sonatinas, and nude cowboys hardly seem so black and white as they would ever get rendered should history ever touch them. The field of twentieth century music history has, via self-consciousness, enacted the rightful process of music history: declare a few leading lights, produce their music ad nauseum, produce their editions, tell their stories, cannibalize that narrative, and move on to the second-tier. Although I should probably start researching more famous composers in order to have a more fulfiling career, I'm having fun right now spelunking through to new footnotes and shaking the mud from my boots.

2 comments:

I'm an old friend of alberts. He lived at my house on Peaks Island on and off back in the late 70's and early 80's. One evening I pulled out my real to real and recorded Albert reading his poetry. It's really some amazing stuff.

Albert was Artist in Residence at Center for Book Arts in NYC 1974-76. He sent and received mail art from there until he moved to Boston. Had an incomparable rant.

Post a Comment