Peter Gillette likes to read and write and play the trumpet and listen. Peter lives in Iowa City, and this is his blog.

Sunday, March 29, 2009

A "Minor History" Of Early Minimalism

Who is Tony Conrad? Well, he's a musician and filmmaker took part in LaMonte Young's Theater of Eternal Music, which I mentioned briefly in an earlier post, and has been invested in retelling the history of early minimalism. Conrad and John Cale (violist for the Theater of Eternal Music and a founding member of the Velvet Underground)--and particularly Conrad--have been engaged in an authorship dispute with LaMonte Young off and on, arguing that the sound of the Theater of Eternal Music rather than his individual compositions constitute a musical birthplace of sorts for minimalism (Peter's thumbnail sketch). Young held on to the recordings.

(For that matter, Young's recordings are so darned expensive even after all these years.)

What's so valuable to me is that I'm trying to find a way to "frame" the career of an admittedly minor figure, Albert Fine, who was in an analogous position--except that he straddled the musical "mainstream/establishment," which makes his eventual career choice--as a conceptual artist and filmmaker (like Conrad), rather than a composer--all the more striking. But Joseph has given me a good strategy for how to highlight a minor figure without making silly claims that lose all perspective, that relate the major figures of the day to them rather than keeping the minor figures in the footnotes of the major figures' biographies--which is good, but "the next step," historically, is underway.

The other interesting aspect of a "minor" history is just thinking about the career of Conrad--filmmaker, conceptual rock musician, purveyor of happenings, composer, violinist, etc... I think of so many of my friends in New York, doing "conceptual" things and working menial jobs, and wonder if some day... I don't know, will they be history? That's a loaded question, and I do appreciate that Joseph explicitly argues against of man-on-the-street-is-an-example-of-large-scale-trope cultural studies leveling of the historical playing field. He focuses on telling a compelling story.

Here are a few pertinent videos. If you want to be a true conceptualist, consider playing all at once:

That's all for now... The book is surprisingly sharp in its discussion of the music, given that it comes from a "non-musician," and the little bit I've read (the first two chapters) are quite promising. Exciting! More later.

Thursday, March 26, 2009

What Is Popular Is Sometimes Right

Beethoven's ninth, Moonlight Sonata, 1812, Handel's Messiah, Tchaikovsky's first piano concerto, Barber's Adagio--psssh! Those people (you know, mindless regional orchestra subscribers and the like) listen to things like that.

I'm playing two concerts next weekend of quite "familiar" music. On Palm Sunday, I'm playing the Messiah, and on Friday night April 3rd, I'm playing in Johnson County Landmark (the world's oddest name for a college jazz band) backing up clarinetist Richard Stoltzman in a Salute to Benny Goodman, at a sold-out Englert Theater in downtown Iowa City. I've been in grad school long enough that I'm beginning to cycle through repertoire: that is, we tried to put this concert on 2.1 years ago, but were foiled due to ice.

It's always an odd feeling in college big bands, because sometimes there's a hold-your-nose kind of culture that comes with "historical" big band music. Ew, vibrato. Ew, simple chord changes. Ew, old people would like this music. And so sometimes I come into a concert cycle pretending to feel that way, but--again and again--I'm convinced that this music, from the inside out, is irresistible. It teaches you how to swing, how to wait, how to hurry, how to hit it, how to hide away.

We're doing a good mix of favorites, small group stuff, cute-stuff, and burning Fletcher Henderson arrangements. I've always been a big Fletcher Henderson fan--my favorite is a ditty of his called Fidgety Feet. It's really wild stuff, inventive and irresistible. And although I'm not playing on this particular tune, "Queer Notions," archaic title and all, is just about the funkiest thing ever done with a whole tone scale:

Then, there's Sing, Sing, Sing. Talk about the cross-sectional writing. Bugle Call Rag--how about that syncopation? "Goodbye" (Gordon Jenkins' Goodman band theme) is sweeter than it is schlocky, and I can never write it off as theme music, since the first version I knew was Sinatra's Only the Lonely reading:

Anyway, I even walk down the street humming the syncopated out-chorus to "Let's Dance." Listen how in this simple--some might even say cheesy tune--the bass and saxes are so far out front of the time, the brass and drums drag it, and Benny is Benny.

What's the effect of that whole tempo game? Go ahead: don't tap your toe.

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Lent n' stuff

So, for Lent, I gave up hamburgers, and I have stuck to it, completely. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’ve had my share of beef brisket, French Dip, Italian beef, etc. But tonight, earlier, I firmly drew the line at counting Patty Melts as an exception, as if rye bread and grilled onions were an odd form of dispensation.

Why hamburgers? Well, first of all, I’m not Roman Catholic or anything like that, and I really didn’t grow up giving things up for Lent. But on Fat Tuesday, I was very hungry, and so woke up and drove to Burger King for breakfast. Then, twice more, I hit up the drive–thru. I felt kind of sick (even though, well, I’m not a very healthy eater since nobody forces me to buy lettuce these days) and guilty, and then realized it was Fat Tuesday. I’m not a big chicken fan (now, the fried batter—that’s something else entirely), don’t really like Turkey, and pulled pork is hard to come by on a daily basis. As a consequence, I’ve been cutting down on my garbage food and, finally, French fries.

But I’m thinking, maybe I should have given up scare quotes, or participating more than five times in discussions during classes, or falling asleep to TV-on-DVD (or TV-on-DVD entirely), or Freecell, or idle contemplation, or spite, or music, or discretionary spending, or unnecessary speech, or purple Vitamin Water.

The other day, in the spirit of Lenten devotional, reached for the Thomas a Kempis book from back in the day, The Imitation of Christ, I once idealistically bought and out of historical curiosity. It sets up some very ascetic ideals for monastic life such as being overly familiar with one another, or speaking unnecessarily--one that really trips me up. I don’t really read that book much.

As a consequence, I’ve noticed that blogging is good for that: paradoxically, anything I blog is stuff I don’t think my friends would want to talk about. It works in theory, but makes for a pretty dull blog.

Yes, this is a post not about esoteric music, although I have been having a tough time not downloading Golijov's La Pasion segun San Marcos

I guess I don’t really talk about my spiritual life much because it’s personal, because I don't want to belong to any club that would have me as a member, or discredit any church or set of beliefs by my association with it, etc. etc. But perhaps a spiritual theme lately in my thought-and-prayer life lately is to allow myself to be troubled by troubling ideas, to not grapple so much, to let difficult ideas be difficult ideas and to appreciate mysteries--whether they come in the form of people, ideologies, or events. That actually has real consequences for how one experiences music, reads books, and interacts with people--even if I am not about to avoid "idle talk" anytime soon. After all, what, then, would I talk about?!

And I'm not going to lie: Lent is the most lucrative trumpet season of the year. So, that's nice.

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

A new blog name, and a new little dinosaur

If you are one of my friends who periodically visits this blog, you may have noticed that I've moved in a more specialized direction. A more professional blog needs a more professional title, because nobody wants to link to "Peter's Blog." And since I enjoy studying American "ultra-modern" music of the 1920s and 1930s, I thought it was appropriate to give Henry Cowell his propers.

On an unrelated note to New Music, I've found my dog's real species, via AP:

Imagine a vicious velociraptor like those in "Jurassic Park," but only as big as a modern chicken. That's what Canadian researchers say they have found, the smallest meat-eating dinosaur yet discovered in North America. This pint-sized cousin of velociraptor, weighing in at 4-to-5 pounds, "probably hunted and ate whatever it could for its size — insects, mammals, amphibians and maybe even baby dinosaurs," according to Nicholas Longrich of the University of Calgary.

Given the description, I wasn't surprised at all that the artists' projection of this new, miniature carnivore looked very familiar to me:

Happy St. Patrick's Day, I think!

Saturday, March 7, 2009

LaMonte Young's "Dream House"

Being an Iowan and not a hip New Yorker, I was not aware that Young is currently producing one of his Dream House exhibitions with Marian Zazeela at the Guggenheim through April 19, 2009 courtesy of the MELA Foundation.

Here's an excerpt from that vintage typescript. In the name of fair use, I've only reproduced 7 sentences:

And in the life of the Tortoise the drone is the first sound. It lasts forever and cannot have begun but is taken up again from time to time until it lasts forever as continuous sound in Drean Houses [sic] where many musicians and students will live and execute a musical work. Dream Houses will allow music which, after a year, ten years, a hundred years or more of constant sound, would not only be a real living organism with a life and tradition all its own but one with a capacity to propel itself by its own momentum. This music may play without stopping for thousands of years, just as the Tortoise has continued for millions of years past, and perhaps only after the Tortoise has again continued for as many million years as all of the tortoises in the past will it be able to sleep and dream of the next order of tortoises to come and of ancient tigers with black fur and omens the 189/09 whirlwind in the Ancestral Lake Region only now that our species has had this much time to hear music that has lasted so long because we have just come out of a long quiet period and we are just remembering how long sounds can last and only now becoming civilized enough again that we want to hear sounds continuously. It will become easier as we move further into this period of sound. We will become more attached to sound. We will be able to have precisely the right sounds in every dreamroom playroom and workroom, further reinforcing the integral proportions resonating through structure (re: earlier Architectural Music), Dream Houses (shrines, etc.) at which performers, students, and listeners may visit even from long distances away or at which they may spend long periods of Dreamtime weaving the ageless quotients of the Tortoise in the tapestry of Eternal Music.

Makes Milton Babbitt seem pretty clear. Unlike the lucky tortoises, you can only go to these installations from 2PM til Midnight, so if you're in New York, go. You'll have a heavy freak-out experience, bro, until you bug out. Dig?

Via MELA, Kyle Gann has a math-nerdy explication and appreciation of the installation he wrote for the Village Voice.

From the thick of the sixties, the Albert M. Fine archives

Editor's note: I meant to make some basic edits to this post, which I worked hard to create, but then ended up deleting it. Oh noes! Luckily, though, I recreated it from my Google Reader feed.

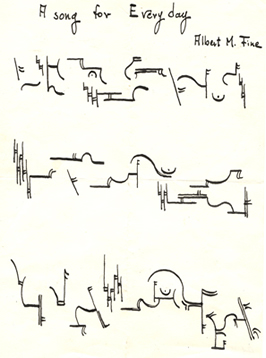

The image to the right is a composition by Albert M. Fine (linked to the UI Special Collections department).

Okay, I will just state outright that goofy, aleatory music from the 1960s is some of the most dated art ever, and it can be unapologetically, unendingly tedious. I've talked about in general in the second half of this post. Nonetheless, as a musicologist training in Iowa City, I've been spending some time in the Albert M. Fine papers in the University of Iowa Special Collection Department's Alternative Traditions in the Contemporary Arts holdings. I first started poking around in the archives during the spring of '07, then didn't for awhile, but now revisited it looking for unpublished material to use as Music Editing exercises.

Archives are good for hording, right? But in the name of collective interest, maybe I'll put a teaser to what can be found here out here on the internet in the hopes that some researcher may have some more information on Fine, and so something musical will appear when you google "Albert M. Fine".

Fine was a clarinetist in an Armed Forces service band stationed in Paris during the early 1950s, where he befriended Ned Rorem (a few of whose letters, tame in light of his voluminous personal writings, of which Mescaline in the Poconos is the most entertaining, appear in the archive) among others. Fine trained at Julliard under Vincent Persichetti (who is a prime example of a composer who we play but seldom talk about. Philip Glass's Grove Article (and if you're still reading by now, you're probably the type who would have access to a Grove proxy log-in) by Edward Strickland lists Fine as a student of Boulanger (which makes sense, given the Rorem/Paris years in the early 1950s) as well as one of Glass's private teachers while they were fellow students under Persichetti.

Before Glass moved to Pittsburgh, he worked at the Yale Transport Company as a "pusher," a fact proved by the identification badge of a thuggish looking pretty-boy, "P. Glass," that Glass mailed to Fine, who had loaned Glass some money previously. Glass's letters are

particularly funny, especially when he refers to the many "block-heads" at Aspen and "boobys" among New York's composers in the summer of 1960. A roll of four mini-photos of a goofy Glass apparently taken in an amusement park's photobooth is worth the price of a Greyhound ticket to Iowa City.

particularly funny, especially when he refers to the many "block-heads" at Aspen and "boobys" among New York's composers in the summer of 1960. A roll of four mini-photos of a goofy Glass apparently taken in an amusement park's photobooth is worth the price of a Greyhound ticket to Iowa City.Also of musical interest: a genial Christmas card from the early 1960s reading "Peter Schikele, Hollywood Composer" where the future P.D.Q. Bach wonders aloud if he'll ever find his niche. (Hint: he did.)

Also of note:

- support from budding young IBM mathemetician NY Phil assistant conductor Stefan Bauer-Mengelberg

- a fascinating correspondence between a semi-famous Soviet conductor, Fine Persichetti, and the Lincoln Center's impresario Mark Schubart that I'll only tease for now (Would that I read Russian), except to say that Persichetti, through his publishing outlets, helped to funnel new-music scores into the USSR during the heyday of the Khruschev thaw. There is a wish-list (David Diamond was the talk of the town) and letters of receipt.

- There are letters to Cage, and typescripts/early scores from LaMonte Young that are the subject of a separate meme.

Fine's scores, largely unpublished, align with some of my recent Taruskin reading that deftly seeks to challenge the way our "histories" are simply chronicles of firsts this, firsts that, and puts anything perceived as "regressive" off to the side. Interspersed in his dated compositions (spanning six years in the early 1960s) are:

- ballet scores for David Waring in the vein of Persichetti (wherein "neo-classic" wind textures frame sonorous but non-tonal melodies)

- eminently playable solo and chamber works for woodwinds that also recall Persichetti's Parables in their idiom

- silly, self-referential songs

- piano works that show the influence of Cage and Feldman (particularly in the way that spatial organization on the score is a device of rhythmic notation)

- Silly, irreverent miniatures (including a horn quartet with a variety of pseudo-Germanic dedications)

- "Game" pieces that experiment in open form according to parameters

- (contains profanity) early fluxus scores, including a notated "happening" for the Longy School of Music in 1965 (that ends with a young girl exhorting the audience: "Dear Audience, Fuck You, You are Now invited to Bug Out.”

- Works from 1965 for pianist David Tudor that are nothing more or less than early minimalism (not "proto-minimalism"), where two constant broken pentatonic "cells," a half-step apart repeat for 30-40 measures at a time and slowly change.

Think, for a moment, on the notion of a fully-notated happening in 1965, the golden-age of happenings, at the Longy School of Music. Even by 1965, this far-out technique was just that: a commodified technique, a set of formal principles useful for generating more music. But looking at one man's unpublished output from this time period, something stands out: the same man is, in the same month, producing music that questions the nature of music and writing eminently playable, impeccably notated, downright neo-classic works by comparison to Fine's work for "24-piece Fluxorchestra."

On the one hand, the score is becoming a visual document rather than an aural schematic; on the other, his friends and colleagues want some music to play and to dance to. Playing-Music and Talking Music. What better way to prove Cage's ascendancy--not to mention the way he's become defanged--than to notice that his dictums were, and are, just another compositional technique? But if this music were to make it out of that archive in scholarly form, which do you think would attract the most notice from scholars, and which from performers?

Like the other minor American composer that I'm researching, William Russell, Albert Fine has been (and will continue to be) a minor prophet unless one makes him into a John the Baptist for a coming Jesus (John Cage, Steve Reich, etc.). Each composer's career nicely bookends Cage's main period of musical creativity (with the exception of some string quartets in the 1980s), anticipating it, perhaps, and reacting to it, perhaps. Each dabbled in the avant-garde styles of their day, even exhibiting some avant-garde predilection for "firsts," before withdrawing to greener (or, in Fine's case, more "cosmic") pastures. Each had a brief and modest compositional output and probably have, in the process of historical darwinism, died their natural deaths.

Fine went on to be more well-known as a visual/conceptual artist. Indeed, his name is listed in a "mail-art" directory from the early 1970s, so among his correspondence are several crude drawings and unexplained postcards from strangers, including a lovely drawing of an afternoon sky by poet Allen Ginsberg and, tellingly, a pornographic playing card featuring a pantsless cowboy sent mailed without enclosure or comment (just return address) from debatably pornographic photographer/right-wing Bogeyman Robert Mapplethorpe in 1970.

Fine seemed to live the boundaries of the question, "But is it art?" and seemed to relish "freaking out the squares." For a couple hours the past couple Friday afternoons, I've put myself in Cambridge during the 1960s, and, leafing through the thick of it, minimalism, flute sonatinas, and nude cowboys hardly seem so black and white as they would ever get rendered should history ever touch them. The field of twentieth century music history has, via self-consciousness, enacted the rightful process of music history: declare a few leading lights, produce their music ad nauseum, produce their editions, tell their stories, cannibalize that narrative, and move on to the second-tier. Although I should probably start researching more famous composers in order to have a more fulfiling career, I'm having fun right now spelunking through to new footnotes and shaking the mud from my boots.

Thursday, March 5, 2009

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Audio Files Part III of III--Music of Talking and Music of Playing

“There are two musics (at least so I have always thought): the music one listens to, the music one plays. These two musics are two totally different arts, each with its own history, its own sociology, its own aesthetics, its own erotic; the same composer can be minor if you listen to him, tremendous if you play him (even badly)—such is Schumann,”writes Roland Barthes in the (famous? the term is relative) opening to his essay "Musica Practica." Barthes is maybe a tad too glib to be of concrete use on many musical topics, but his general thesis about music and the body seems to have been borne out in the much-talked about (unread by me except in various reviews and a couple excerpts) recent book Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology . Boccherini is perhaps a better test case than Schumann, because—frankly—poor Mr. Schumann had a sad enough life without being on the business-end of a cheapshot.

(Let me pause for a moment: how is it that MS Word recognizes Schumann and Boccherini as words, but still does not believe that anyone would have reason to use the word “chromaticism”?)

I won’t get into the Boccherini book (since I only perused it once while babysitting at a professor's house), but I will propose an emendation to Barthes’ division of musics: it is not the music one listens to, perhaps, but the music one talks about. Now, an eminent Liszt scholar swung through Iowa City a couple of weeks ago and gave one of those delightfully casual British chats during which I found myself trying, in vain, searching the room for a servant to fill my empty sherry glass. He had some dismissive words for “musicology” as a discipline that ignores performance—and, frankly, he has a point. A musicology professor then came in the next week with a prepared quotation from this scholar to rib the theorists: “Music needs music theory like birds need ornithology.” That statement is, of course, silly on its face: if birds didn’t have ornithology, then how would we better protect their habitats in an age of industrialization? Clearly birds need ornithology this day and age. As for the music, I don’t know.

But is the music we don’t play really the music we “listen to”? I think, rather, it’s the music we talk about. Some music—like Kazdin’s, or the more elegant structures of Babbitt—are not exactly sounding documents as much as they are living artifacts of a practice, or animations of a pedagogy. That’s of course a very reductive way to consider Babbitt, but I don’t mean it reductively: in Babbitt’s early piano works through Philomel through his goofy, raggedy faux-jazz, a certain manic joy, contained by means of a charmingly put-on decorum, sneaks out, and that—when I listen (instead of read or write) to his music—has been creeping out in increasing measures. It is idea manifest, and it comes to life not in our puny little ears but as a memory to be subsequently taken in at deeper and deeper levels. It’s as if a special species of bird evolved, a bird with the most elegant innards one has ever seen, a bird that evolved according to our ornithological fetishes, a wondrous bird that exists as if only to give bird-watchers a peculiar pleasure, a bird eager to be dissected and reassembled according to our wishes. Perhaps Kazdin is not on the same level, as a composer, but it too seems to belong in the realm of talking-music—although, one thinks, that combination of instruments is so specific that it was probably written as a gift, to be a slight sort of playing-music. (Hmm… he did an awful lot of engineering for the Philadelphia Orchestra brass…)

Albrechtsberger and Saint-Saens: when are the last time that you have heard these discussed in an academic context, without—in Saint-Saens case, at least—a pre-emptive apology of sorts? What Perspectives of New Music issue doesn’t mention Webern, and—perhaps I’m missing something—how many “John Rutter Issues” has PNM had? Now, do some crazy math with me, new-music lovers: have you ever tried to imagine how many people, per composer, have actually performed Webern in concert in public, even badly? How about Babbitt, Boulez, other warhorses? My guesstimate is: 20,000, 600, 1,200, respectively. How many have sang Rutter works? If you count congregations, I would guess the answer would be in the multi-millions. That doesn’t make either one any more worthwhile; my hypothetical is just meant to underscore the split between music we prize for what it sounds like and music we prize for what we can say about it.

Think about the practical utility of a Voxman publication, for instance: wouldn’t it be a trip to analyze an entire book of Voxman duets—like, really analyze it with lots of silly charts and graphs that find some sort of John Nash-style “hidden tonal network” within a collection? And yet, it would be quite a fine dissertation in some ways. I remember hearing a job talk a handful of years ago where a Doctor of Trumpet presented his dissertation research while applying for a job. He was a very nice guy, and I’ve forgotten his name, so I’ll try to keep identifying information to a minimum. His dissertation was on a serialist trumpet concerto written in the eighties by a composer whose anyone still reading this blog would recognize. His thesis? “This is a masterwork that deserves a permanent spot in the trumpet repertoire.” When politely asked about his experiences playing the masterwork that deserves a permanent spot in the trumpet concerto repertoire, or a real-time sample of his favorite bit to play, the nice man politely demurred. There’s nothing wrong with those dissertations; somebody’s got to be the expert on Composer X’s trumpet concerto, and that is a useful purpose of the dissertation as a genre. And it should be added that, from what I saw of the score, I would never be able to play it, half-tempo, down an octave, or otherwise. But that’s certainly one dissertation archetype that demonstrates a split between playing-music and talking-music. (The guy who got the job didn’t have lots of charts and graphs; he just came in like he owned the place—because he did—and taught his butt, and our butts, off.)

As I’m drawn to kitsch, that sometimes takes me dangerously deep into talking-music territory. I’m thinking of a composer like the Bohemian-born American composer Anthony Philip Heinrich (1781-1861). I may very well be the only person under the age of 40 in the world today who owns a copy of William Treat Upton’s definitive (er, only) biography of Heinrich. Heinrich is terrific fun to talk about. He’s a swindler, a liar, a scammer, occasionally showing an erratic streak that could possibly intersect with “genius” if one constructed a Venn diagram of the two topics side-by-side. His music is self-absorbed, amateruistic, but overblown and impossibly fussy. As kitsch, it’s a terrific listen. (I also own, I confess, the one CD release of his orchestral music. I found it on a library discard pile for a dollar.)

And as an exercise, I tried playing and singing selections from On the Dawning of Music in Kentucky, his seminal song collection. Maybe in the back of my mind, I thought it could be a Harry Partch, corporeal music kind of thing, that the music would only come alive if I tried to understand it from the point of view of a singer. Now, I’m not a great singer, and I’m a worse pianist, but this was the most awful experience I’ve ever had wading through a piece of music. I’d rather sing a Latvian phone book set to the tune of Babbitt’s Philomel than wade through Heinrich’s awkwardly-phrased, compulsively over-ornamented melodies ever again--as "the music one plays."

My good friend and office-mate Stevie last year is a singer/musicologist, and I think I tried to convince her to sing them at one point, but it’s music that resists performance—and yet Heinrich published these songs in aggressively over-promoted collections available through subscription for the express purpose of domestic music-making. If Sherman’s March To The Sea torched some Heinrich songbooks along the way, it was in that respect a merciful act indeed. Denise von Glahn performed a virtuoso feat by saying something meaningful—nay, illustrative—about Heinrich’s skills as a tone-painter in her The Sounds of Place, leading me to the false hope that I too could say something meaningful about Heinrich’s music. But some obscure composers are notable more for what we can say about the fact of their existence rather than the content of their music. That's not right; but to do it justice, you need some mode of understanding (like von Glahn's spatial/landscape metaphors) that can vindicate the music, in a sense, or free it from its failings in one context or another.

Still, I feel a compulsion to unearth, edit, publish, and yes—YES!—perform Heinrich’s storied Klappenflugel (keyed bugle) Concerto, storied in that it… exists. It gets a few lines in The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments and had a modern premiere a decade or two ago in Australia. Again, great fun to hear, and so many things to talk about concerning Heinrich.

Then again, I could even talk about Glen Campbell.

Well, last weekend I saw an awesome Boulez/CSO concert from the terrace, so I might post about that in the future. Also, my dog Maddy's been begging quite a bit, and there are some funny stories about that that I might blog. And finally, I just bought one famous and fearsome musicological giant's latest collection, many of his "public writings" and occasional reviews. (I've purposely avoided putting his name in the post itself for fear that GoogleAlerts would trigger... nevermind.) It's such wonderful reading, but I don't know if I dare post about it. My one favorite so far, that caused me to excise a large section of this post and re-think it for later, was the dead-on essay "'No Ear for Music:' The Scary Purity of John Cage."